It’ll be twenty one years ago this Thursday that I heard the words: “It’s what we feared the most.” Sitting on the exam table, the air was knocked out of me like someone slammed me in the back. That day I’d had a lumpectomy on my new surgeon’s lunch hour. He squeezed me in. “The margins are not clear so we’ll have to do more but tomorrow I’m leaving for India for six weeks. You’ll need a surgeon, a reconstructive surgeon, a radiologist and an oncologist.” “But I’m a backpacker!” as if that gave me some kind of immunity. “And next year you’ll be backpacking as a breast cancer survivor.” Ok, I thought. I can do this. But, there I was, diagnosed with breast cancer and left to figure it all out on my own. Though the pathology report called it a slow-grower, I was anxious to get this alien life form out of me, especially before it spread. I chose a mastectomy over a lumpectomy to greater ensure that I was done with this disease and started looking for a surgeon who was not headed for India.

I’d first felt the lump two and a half years earlier and had it scanned and ultrasounded and they deduced that it was a fluid filled cyst. I watched it for two and a half years until I leaned on it in my hammock on a backpack trip to get grounded three days after my daughter came out as gay, and it hurt. The skin was dimpled where the lump was. My nurse practitioner gasped when she saw it. She’d never hugged me good-by before. An in-office biopsy was quickly scheduled for after hours at a surgeon’s office. Having all afternoon to fret, I prepped with two slices of pizza and two glasses of Cabernet. The biopsy resulted in a bad vaso-vagel reaction with lots of red pizza in the trash can but no biopsy sample. A lumpectomy scheduled for a week later would get a sample for a diagnosis.

I learned that there was a new technique called a Sentinel Node Biopsy which would prevent me from having lymphedema at altitude, a common problem when they remove all the lymph nodes in your armpit during the mastectomy. I called around to get a doc that would perform a Sentinel Node Biopsy along with a mastectomy. It was a common procedure in the LA area but I found only one doc with experience in the SF Bay Area. I would call a hospital to see if it was a procedure in their repertoire and, from John Muir in Walnut Creek, the sweet speaking lady on the other end of the line said, “Yes, we do it, then we remove all of them.” I said, “Well, what’s the point of that?” “Don’t you want to be part of the group that the docs practice on so women in the future can have it done?” I reflexively yelled, “NO!” and slammed down the phone.

I interviewed four plastic surgeons in their very snazzy offices. You can tell by their office how lucrative their practice is. One reached into a cabinet behind his mahogany desk and tossed a quivering blob of gel onto the desk top. “That’s what we use,” he said of implants. I starred at it, touched it, and lifted it up in the palm of my hand. That’s about ¾ of a pound,” I said. “Yep.” “My hammock weighs about that much!” I was a AA and they all wanted me to go up in size. (Insurance is obligated to even up both sides.) While discussing it with a nurse, she unexpectedly moved in close, unbuttoned her blouse and showed me hers, clearly a perk of her employment, “You could have THESE,” she said. I recoiled only wanting to stay alive.

They all had photo books of their patients pre and post-surgery. They were all very proud of their work. They promoted fancy tram-flaps, and procedures where they wrap your back muscle around and fashion a boob out of it. “But I use my muscles,” I said. That didn’t seem to matter to them as long as it looked good in their portfolio. Me? I just wanted to stay alive and use my body if it was still here. In my vulnerable state I chose the plastic surgeon who said the magic words, “I’ll take care of you.”

The surgery was Dec. 9, my father’s birthday, but I had distanced myself from my family for about 8 years. Nervous but anxious to get the alien life form out of me and on to chemo and radiation and the rest of my life, I arrived having already had a drunken going away party for my breast with girlfriends at a local bar the night before. The next thing I remember was a hot iron on my chest, like the kind steam comes out of when you iron shirts. I could see the oncology surgeon and the plastic surgeon with their blue gowns and head nets on. My eyes were open but I could not move. The pain was searing. Then a mask moved over my face and I disappeared again. From then on I always tell the anesthesiologist not to take a nap on the job.

After a month of Jackson-Pratt Drains hanging out of my side, they were yanked, my skin having grown into them, and an attempt was made to fill the tissue expander for my new boob. But it had been installed upside down and instead of the needle hitting the port, it went through my skin and hit a metal plate… five times. Now in chemo, where they drip drugs into you that make you not heal, my oncologist gave me permission to have a new tissue expander correctly installed but made me promise that I would not get it infected.

Oh, Karen… I later told Rick to chain me down and let me howl the next time I want to get into the hot tub at the YMCA with an open wound: Another surgery to remove the tissue expander and clean out the sewer in there. Coulda died.

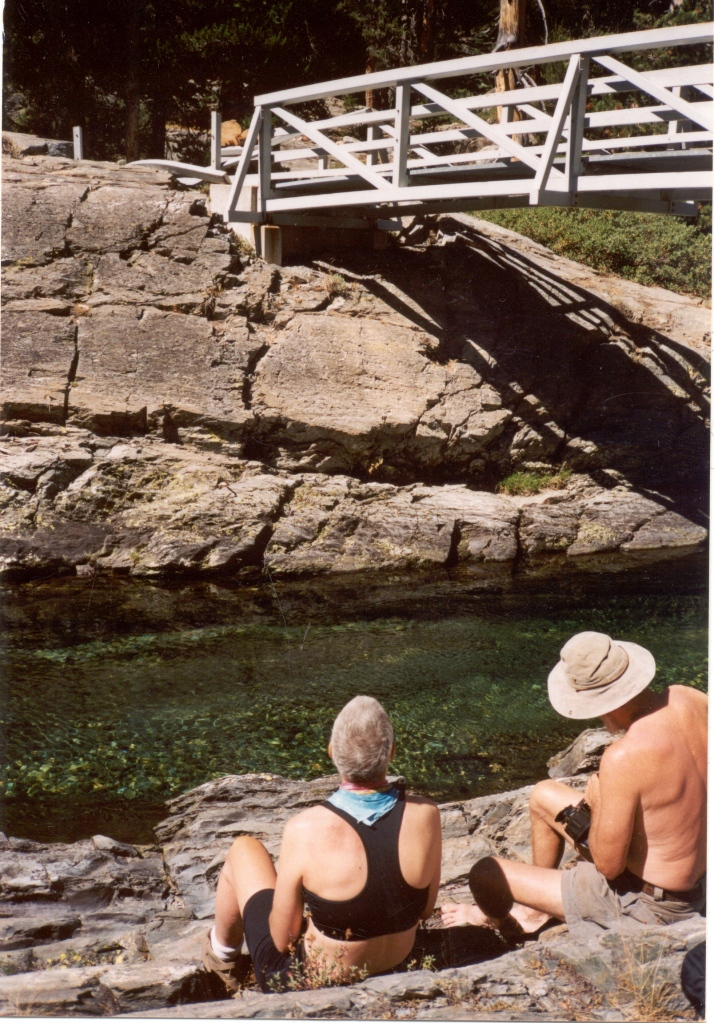

So then, six months of two types of poison dripped in to kill whatever was left and five weeks of radiation later, I was back backpacking, literally. I didn’t belong on the eight-day trip off-trail around Mts. Banner and Ritter with my bald head and armpit peeling like the skin off of pudding due to the radiation burns, but I needed to be there, in my wilderness home with my tribe. Besides, I had to be there to reduce my husband’s dislocated shoulder when he slipped on a steep slope, instinctively grabbed his poles, and jerked his arm out of the socket.

A few more dislocated shoulders, surgical repair, a lost gal bladder, and a hip replacement for me and we’ve been happily backpacking ever since. I’d go in for my check-ups every six months, mostly to share my latest adventures with my doc. I’d stroll in all tan and strong and healthy past the bald, gray-skinned people all hunched over barely alive. What was I doing there?

I got twenty great years. That was forty great check-ups. I’m even on my third oncologist, having outlived the careers of two of them.

“It’s a gut punch,” my doc said today, “these late recurrences. You go through all that and after a while you just forget about it.” Exactly, I thought.

Oh My!!! What a journey! So glad you are here and that you share your journey. Beautiful words! Cheers to you for another anniversary!

Karen! Just discovered your blog. What a very fascinating account. I am so glad you are telling your story, putting it out there. The anesthesia awareness episode, you are the first person I’ve personally heard of who has also experienced this! NOT fun. (and for you on top of everything else!!) Also, I love the topo map choices in your sidebars, country I know very well. Yes, you’ve lived very well, and I think that has contributed to your 20 years of great checkups. Power to you, and thanks for sharing.

Hard to find the right words to say–you are such a trooper and your story is an inspiration.

What une histoire, really not to be repeated, but given that you did, I am over-the-moon that you have kept your amazing fortitude, exceptional courage, and metal-jacket constitution. I have had my share of horrific, excruciating pain (bedridden for 7 months), but I could never wish what you have gone through on a worst enemy, let alone someone we all love dearly. You ARE an inspiration and I trust your blog writing is deeply cathartic. Perhaps a book in the not-too-distant future. Sending buckets of love and socially-distanced hugs and kisses. ❤️☀️🌈