In my book, I‘ve already gone over the California map and at this point, my clients have a good idea of where they are on the planet.

The next map I bring out is the park map that the rangers hand out to everyone at the entrance stations. I point out the roads and I lay my pinky finger on Yosemite Valley. “This is where 96% of people who come to the park go. They think that if they’ve seen Half Dome, they’ve seen Yosemite.” I do my best imitation of Chevy Chase in National Lampoon Vacation where, at the lip of the Grand Canyon, he puts his arm around his wife, and nods at the view for two seconds, before herding the kids back to the car for the next destination. Smearing my hand over the rest of the map, “From our high vantage points you are going to see it all.” I see smiles of privilege and anticipation.

“This is a nice map if you’re in a car. You can see the roads, the Visitor Centers, the trails, a few lakes. But it can be deceiving. See how Glacier Point here looks really close to Happy Isles? Well, they are really close… as the crow flies. Two boys told their parents they were going to hike to the ice cream stand at Happy Isles from Glacier Point. They ended up ‘coptered off a ledge because, even if it looks close on the map, it’s 3,000 feet down. If they had a topographical map and knew how to read it, they would never have made that mistake.

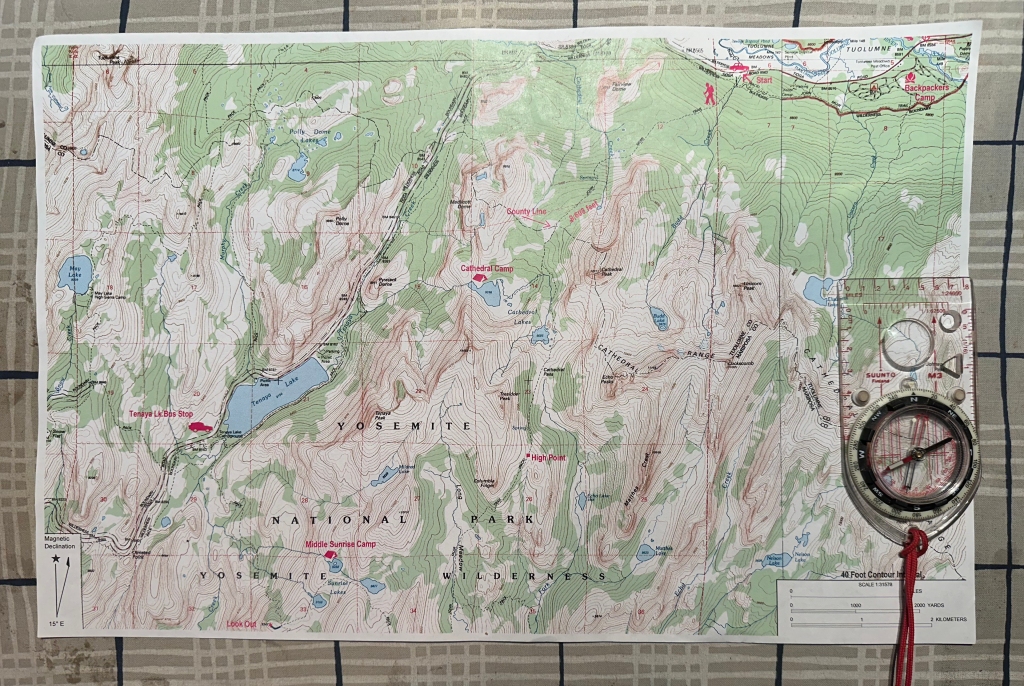

With that, I haul out the custom map I have printed for each of them. I point out the scale, how two inches on the map equals one mile on the land, that the top of the map is the north edge, and that the space between contour lines, the contour interval, is forty vertical feet.

“This map has a lot of squiggly lines all over it. It’s easy to get overwhelmed but I’ll teach you how to read it, what’s important, and what to ignore. In Girl Scouts they teach how to take a potato and slice it vertically, then take each slice in order and draw around it on a piece of paper so there’s a bunch of concentric ovals. They name it Mt. Spud. On our map, the space between each line on Mt. Spud’s slope equals forty feet.” I point out a peak on the map and they see the concentric circles. “That’s what peaks look like. The closer the squiggly lines, the steeper the slope is. This is a good thing to look at when checking out your route to see where it will be a hard uphill, a steep downhill, or an easy stroll.”

Pointing out the contour interval always reminds me of the eight-day trip I took with friends off-trail on a loop around Mt. Ritter near Mammoth. It was in 2000. I’d had my last day of radiation for breast cancer the day before the trip. I wasn’t in the best of shape and the radiation burns in my armpit had my skin peeling off like the skin off pudding. We’d pieced together four USGS topo maps to cover the area of the trek. Pre-trip, I kept wondering how we were gaining all the altitude to cross 11,000-foot North Glacier and Ritter Passes. I didn’t see it in the steepness represented by the topo lines. Finally, on the last day, I realized that the map covering the peaks, unlike the rest of the area, was all in meters, not feet. The contour interval was 20 meters, not forty feet. The area we were hiking in was all one and a half times as steep as we’d planned!

Holding up my water bottle, “On this planet, water is always in the lowest spots.” Giggling. “Blue blobs surrounded by concentric circles are lakes.” Much nodding. “These blue lines are creeks or rivers. They always flow downhill, and the topo lines always point in a “V” upstream. By looking at the creeks you can tell which way the slope runs – uphill or downhill.

“Now the green is not grass. It’s trees. Maps were initially made by the military for effective engagements, and they marked in green areas with enough trees to hide a battalion (300-1000 soldiers). Most of these white areas on the map are mountainous areas above tree line but there are also flat grassy meadows designated white, because, while they may look green in real life, there are so few trees. I camp in a hammock strung between two trees, so I like to know where the trees are and aren’t.”

I have them draw our route on the map by following the trail with marking pens, starting where we’ll park our cars at the Cathedral Lake Trailhead, stopping for our first night at Cathedral Lake, and for our second at Sunrise Lake. They follow the steep trail crossing tight contour lines down from the three Sunrise Lakes to the bus stop at the west end of Tenaya Lake where we will hop on and return to our cars. “What about bus fare?”

“You paid it last April fifteenth.”[1]

Next, we step away from the table and I ask, “Anyone have any idea where north is?” Maybe one will know. Usually none. “This is the most important thing I want you to learn. Get out your compasses. We’re going to find out.”

In the beginning, I used to teach a lot more of everything in a lot more detail. I taught triangulation and how compasses were invented and how to make a simple compass with a leaf, water, and sewing needle, and how to read shadows, the sun, and stars. It wasn’t about me wanting to look smart by how much information I could throw at them. I wanted them to feel like they got their money’s worth, and I feared their disappointment if they felt they didn’t get it. At the end of a trip, I asked them where north was, and no one could tell me. So, I asked myself, What is it I want them to take away with them? I want them to be able to find north. I wanted them to take away something foundationally useful.

Much fumbling and running back to packs. Once in their hands, they hold their compasses tentatively, like they’re some exotic animals they’re not sure which end will bite. “Your compass is like your heart. It tells you where your True North is. Don’t leave home without it.”

“Let’s go over the parts of a compass.” From the bottom layer to the magnetic needle in dampening liquid on top, I point out the base plate, the index point, the direction of travel arrow, the bezel, the declination scale, the orienteering arrow, meridian lines, and the magnetic needle.

“First, we’re going to adjust the declination on those compasses that have a declination key.”

Wha?! I can see their brains turning into Maytag washers on spin cycle. “Declination is just a big word that stands for the difference in angle between true north and magnetic north. Remember those little compasses you got as a party favor at birthday parties when you were a kid?” Heads nod. “And little Tommy’s mom got in your face with wide eyes and a freaky red lipstick smile and told you, ‘It’s magic! It always points north?”. The whole group is now a bunch of six-year-olds wearing pointy paper party hats with that itchy elastic band under their chins and I abruptly bring them out of their trance: “Well, they lied! It does not point north. It points to magnetic north!” Like when teaching about where the rivers start, the first time I explained this I was caught off guard by my intensity.

The first time I, myself, learned this, I was flabbergasted. How could all these adults have lied to generations of children? Did they think we were all stupid? Hell, I didn’t even know what north was! Why didn’t adults take the time to teach me anything? Did they figure that I already knew it? Then I realized that they didn’t even know it themselves. How could they teach it?

Declination totally explained the time, early in my hiking career, when I was sitting on top of the pass between Cascade and McCabe Lakes. No matter how I bent the map, my compass pointed at Mt. Dana still read about fifteen degrees off as compared to my reading on the map. Of course, misinformation, presented convincingly, became a main emotional trigger for me as an adult, and not just from the compass and the drips off snowbanks, but so many things.

. I continue: “Magnetic north is deep within the Canadian Arctic and the magnetic needle on your compass points in that direction. True north is where the North Pole is.” I show them the little symbol in the corner of the map that indicates the degrees of declination for the area covered by the map. “In different areas of the earth, the declination is different. Out here it’s fifteen degrees east. At the longitude of Wisconsin, It’s zero. It’s called the Agonic Line. And in New York, it’s thirteen degrees west.” I show them a map of the declinations in the US. “So, if you use a compass, check the declination on the map of wherever you are and adjust your compass accordingly. And, the declination is changing over time as the iron core in the Earth moves about fifty km a year toward Russia. It used to be seventeen degrees when I started backpacking. Now it’s fifteen.” Suddenly, our knees wobble like we’re on an unstable spaceship flying through the Universe… We are.

“Now everyone, rotate the bezel so that north is at the top of your compass, pointing at the index line. With north pointing forward, put the south end of your compass in your belly button.” It amazes me how unquestioningly everyone does this, as if it’s perfectly normal to put a compass in your belly button. “Rotate your body so that the red magnetic needle lines up with the red-outlined clear orienteering arrow. It looks like a red-roofed shed. We call this putting red in the shed. For those that don’t have an adjustable compass, line up the needle with fifteen degrees.” Looking at their belly buttons, everyone is now facing true north.

“Now aim your left arm at true north.” Arms fling straight out. “That’s the direction of the North Pole where Santa Claus lives.” All smiles, they giggle side-eyeing each other, connecting with a deep shared knowing. “Now, point your right arm at fifteen degrees.” I now have twelve people all looking like they’re in the middle of a Tai Chi class. “That’s magnetic north. If you didn’t adjust for the declination, you’d be off by more than a mile after traveling only five miles.” For the first time in their lives, they feel like they have a compass that’s actually helpful. “Now tell me, where south is.” In unison, twelve bodies rotate 180 degrees in . “How about east? west?” My mission is accomplished.

Now, back to the topo map on the picnic table: “Let’s orient the map to the land.” I place the map flat and show how to avoid the metal bolts in the table that can throw off the magnetic needle. With north still pointed to the index point, I place the right edge of the compass, on the east edge of the map and, grabbing a corner of the map, I rotate the whole shebang until red is in the shed. “Now the map is oriented to the land. We are here.” I point at Lembert Dome Picnic Area on the map. Waving my arm to a pointy peak south of us I ask, “What peak is that?”

Folks gather around and I hear, “Unicorn Peak!”

There’s a lake on that slope but it’s in a depression so we can’t see it. “Where is it and what’s it called?”

“Elizabeth!”

“What peak is that over there?”

“Cathedral!”

“That’s where we’re going today. See the lake next to it on the map? That’s where we’re camping tonight. Now you know more than most of my friends do about map and compass. They mostly sit around and argue about where they are.” Proud smiles and a feeling that they just might be able to handle this trip.

“The other thing I want to teach you is about baselines. No, it has nothing to do with baseball. A baseline is a known entity on the land: a road, a creek, a lake, a trail; something physical that you’ll know if you run into it. On this trip, we will always be traveling south of Highway 120. If you ever get lost, and you won’t, but if you did, you could always point your compass toward north, follow it to the road, put your thumb out, and hitch a ride to a burger at the Tuolumne Grill.” Laughs and relief all around. “Whenever you go hiking, you should plan a baseline you can shoot for, just in case.

OK. Let’s throw our stuff in the car and drive one mile down the road to Cathedral Lakes Trailhead. Pull up behind and follow me.”

[1] No longer free.

Copyright Jan. 14, 2024 by Karen Najarian.